Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome

Pellegrini Stieda syndrome is a rare condition of the knee that develops after an injury to the inside of the knee. This is at the level of the medial collateral ligament, or inner ligament of the knee. These complaints show how the body sometimes responds to injury in unexpected ways. Namely by depositing calcium in the damaged area. This process is called calcification and results in a calcified structure that is clearly visible on imaging. Although the image is often impressive, it does not immediately mean permanent damage or impairment. Many people recover well with a targeted approach. The syndrome highlights how close the relationship is between strain, tissue repair with sometimes excessive calcification in response to injury. In this article, we discuss the background, cause, diagnosis and treatment of Pellegrini Stieda syndrome. We show why this condition can be important despite its rarity.

What is Pellegrini Stieda syndrome?

Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome is a condition in which calcification or bone formation occurs on the inside of the knee, usually after damage to the medial knee ligament. This calcification is often at the attachment of this ligament to the thigh bone (medial femoral condyle) and can cause annoying symptoms when bending or stretching the knee. Stiffness of the knee can also occur and especially when starting movement.

This syndrome is named after doctors Augusto Pellegrini and Alfred Stieda. Not to be confused with the mineral water Pellegrino. Pellegrini was an Italian surgeon working in Florence. In 1905, he was the first to describe a case of calcification on the inside of the knee after a traumatic injury. He linked this calcification to damage to the medial collateral ligament. Stieda was a German anatomist and surgeon. In 1908, he described a similar calcification on the inner side of the femur just above the knee. He stated that it was a calcification at the attachment of the medial ligament. He too linked this to an injury, making the picture more clinically recognisable.

However, as with many other discoveries in the medical world, there was an earlier description. Back in 1903, German radiologist Köhler recorded this calcification on image. His observation received little attention at the time because there was not yet a clear link to symptoms or knee injury. It was not until Pellegrini and Stieda linked the calcification to an injury to the medial knee ligament a few years later that it became clinically relevant and their names became attached to the syndrome. We now know that the cause of this calcification is often more complex than what Pellegrini and Stieda suspected at the time. An important difference is that we speak of Pellegrini Stieda syndrome when someone actually has symptoms. The Pellegrini Stieda sign only refers to what we see on an X-ray without necessarily including pain or restrictions.

The cause of Pellegrini Stieda syndrome

The exact cause of calcification is still much debated. It is often thought to be due to damage to the medial knee ligament, but this does not always appear to be the case. On imaging examination, no clear structure can be identified as the source in about half of the cases. Also during surgery, in almost a third of cases, no specific spot is found which is the exact reason for symptoms.

Besides the medial knee ligament, there are other nearby structures that could potentially cause these symptoms:

- the superficial or deep part of the medial knee ligament,

- Medial patello-femoral ligament(ligament between kneecap and upper leg)

- the medial calf muscle (gastrocnemius)

- the adductors on the inside of the thigh,

- the vastus medialis of the quadriceps

All this shows that the cause of a Pellegrini stieda syndrome is probably not always the same reason, but can take different forms. Thus, it is rather a collective term for calcification on the inside of the knee after an injury.

What is calcification?

Calcification In the context of Pellegrini stieda syndrome, calcium-like substances are deposited in the tissues of the knee, particularly in or around the medial knee ligament. These calcium deposits often consist of crystals of hydroxyapatite or calcium pyrophosphate. Sounds complicated, but these are simply bodily substances that also occur in healthy bone tissue.So this process begins in response to an injury or overuse, with minor damage triggering this.

In the first weeks after the injury, the body may react with a local inflammatory response. Instead of the desired connective or scar tissue, the body then starts depositing calcium particles in the damaged structures. So we call this calcification. Calcification in this case is not active bone formation as in a bone fracture, but a process in which soft tissues slowly harden by precipitation of calcium salts. This makes the surrounding tissue stiffer, less elastic and possibly more painful.

When calcification continues and turns into ossification, a more hard structure actually forms. At this stage, a network of bone formation becomes visible at the edge of the calcification, recognisable on an X-ray, for example.

The total duration of the process is around 5 to 6 months on average. In some cases, the calcification remains present without many symptoms. So in this case, we speak of a Pellegrini Stieda sign and not a Pellegrini Stieda syndrome.

The inner ligament of the knee

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is an important structure of the knee and consists of two parts. A more superficial part and a deeper part. The superficial structure is on average 10 cm long and runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial part of the tibia. During its course, it crosses the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus and is separated by a bursa that reduces friction. This is primarily the function of bursas to separate structures and reduce friction. Under this inner ligament of the knee also run the medial blood vessels and nerve tissue of the knee.

The deeper part of the medial ligament of the knee is shorter and is closer to the bone. This ligament comes from the medial joint capsule and attaches to the medial meniscus and the upper part of the tibia (shin bone). This part lies deeper towards the joint and is directly intertwined with the internal structures of the knee.

The long fibres of the superficial MCL resist valgus stress (folding the knee inwards) and external rotation of the lower leg. The deep part of the MCL also supports the anterior cruciate ligament in resisting anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur.

This complex anatomy and interplay makes the inside of the knee susceptible to injury. After trauma or repeated overuse, damage can occur to the ligament and joint capsule of the knee. This can be a reason for calcification in this region.

Diagnosis of Pellegrini Stieda

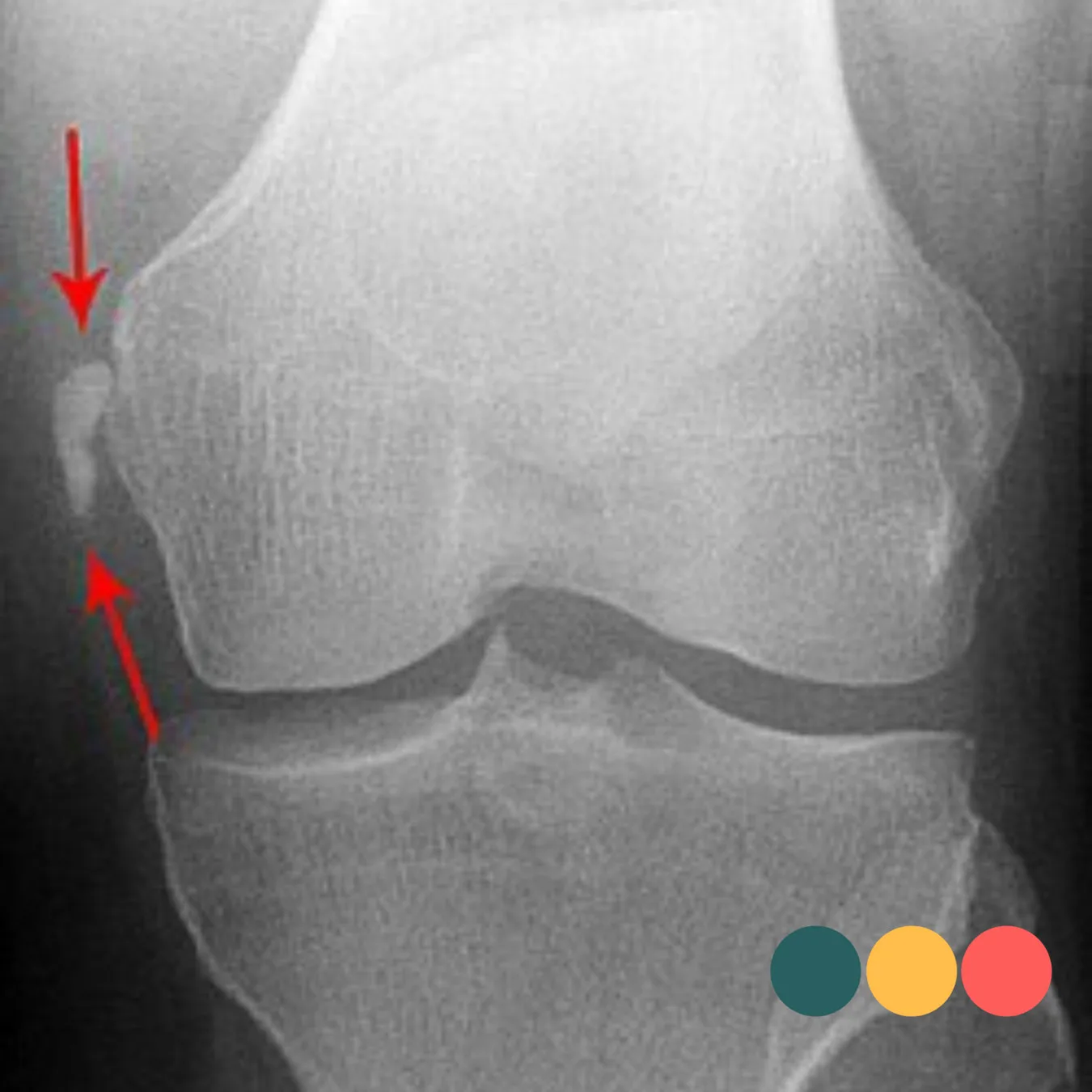

Diagnosis is made by a combination of radiological and clinical examination. Radiographs form the basis of the diagnosis and show characteristic calcification at the level of the upper attachment of the medial ligament to the medial femoral condyle. This bone formation has really specific features that should be easily recognised.

A mri-scan can provide a more comprehensive analysis of the medial knee ligament and surrounding structures. Often, the medial ligament is also affected and thickened on these images. An MRI is especially useful when the abnormality is not clearly visible on an X-ray, but an X-ray is the most commonly chosen option to map this injury in most cases.

Also a ultrasound examination or musculoskeletal echo can provide more clarity here. With ultrasound, you can visualise structures around the knee well and do so directly during the physical examination. Calcifications in Pellegrini Stieda syndrome are often recognisable on ultrasound as a bright white (hyperechogenic) structure with batting shadow. Any swelling or fluid around the ligament is also visible. Ultrasound can therefore help to quickly and specifically assess whether there is active irritation.

A recent classification distinguishes between four types, depending on their shape and relationship to surrounding structures such as the femur and tendons at the medial knee angle:

- Type I - Beak-shaped pointing downwards and connected to the femur: the ossification arises at the attachment of the MCL to the femur and grows downwards towards the ligament.

- Type II - Drop-shaped, also directed downwards but without contact with the femur: the calcification lies in the course of the ligament itself, separate from the bone.

- Type III - Elongated and facing upwards: the ossification is located in the tendon of the adductor magnus, which may indicate involvement of other structures besides the medial knee ligament.

- Type IV - Beak-like, but now facing upwards, with the base at the bottom against the femur: this variation extends upwards from the femur into both the medial ligament and tendon structures, including the adductor magnus.

Treatment of Pellegrini Stieda syndrome

Treatment for this syndrome is usually done step by step, starting with the least invasive options. Should this be insufficiently effective, the options for further treatment are considered in stages.

The first step in the treatment of Pellegrini-Stieda syndrome consists of a combination of rest, adjustment of daily activities and physiotherapy. The goal in this phase is to reduce ligament irritation, restore knee function and prevent further overuse. Activity modification means temporarily stopping movements that provoke pain, such as intense exercise, deep squats or frequent stair climbing. Instead, ways to keep the knee active are sought, for example, by cycling more with low resistance or controlled exercise therapy of the quadriceps and hamstrings.At the same time, in case of pain, anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used to reduce swelling and irritation around the medial ligament.

When symptoms persist despite physiotherapy, rest and medication, a corticosteroid injection be considered. This injection is often placed under ultrasound guidance to bring the active substance as close as possible to the irritated tissue.

Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory drugs and can help reduce pain and swelling. The relief of symptoms usually occurs within a few days and may allow a better return to the exercise programme. This injection should always be carefully considered and performed by a doctor with experience. Repeated use of corticosteroids is not recommended because of possible adverse side effects, such as localised tissue damage or ligament weakening. It is intended to support rehabilitation when other measures have not had sufficient effect.

When symptoms do not respond to treatment, surgery may be considered. Here, the calcification is surgically removed and when the ligament is severely damaged, the medial ligament is sometimes repaired.

Beneficial outcomes in calcification of medial ligament of the knee

Pellegrini Stieda syndrome is a relatively rare but treatable condition in which calcification develops on the inside of the knee after injury to the medial collateral ligament. Although the symptoms can certainly be unpleasant, the prognosis is usually favourable.

Physiotherapy often adds value in the recovery of these symptoms. Through targeted work on mobility, muscle strength, the knee can regain functional load-bearing capacity. Treatment focuses on restoring mobility, strengthening the thigh muscles (especially quadriceps and hamstrings). If symptoms persist, an injection or surgery can sometimes help. Fortunately, the chances of full recovery and return to daily activities or sports are very high.